Sometimes maneuvers for H-BPPV don’t seem to work, and this is especially true for the apogeotropic type, when the eyes seem to beat toward the ceiling when lying on your side. It’s very rare to have this happen. Most of the time, lying flat on your back until the dizziness stops and then doing one of the maneuvers for H-BPPV is enough. About 1 in 100 people, however, will have particles that get entrapped in the canal. Because they are stuck, they can’t be removed easily with a simple maneuver.

Continue reading “H-BPPV and Entrapped Particles”Why is HBPPV such a problem?

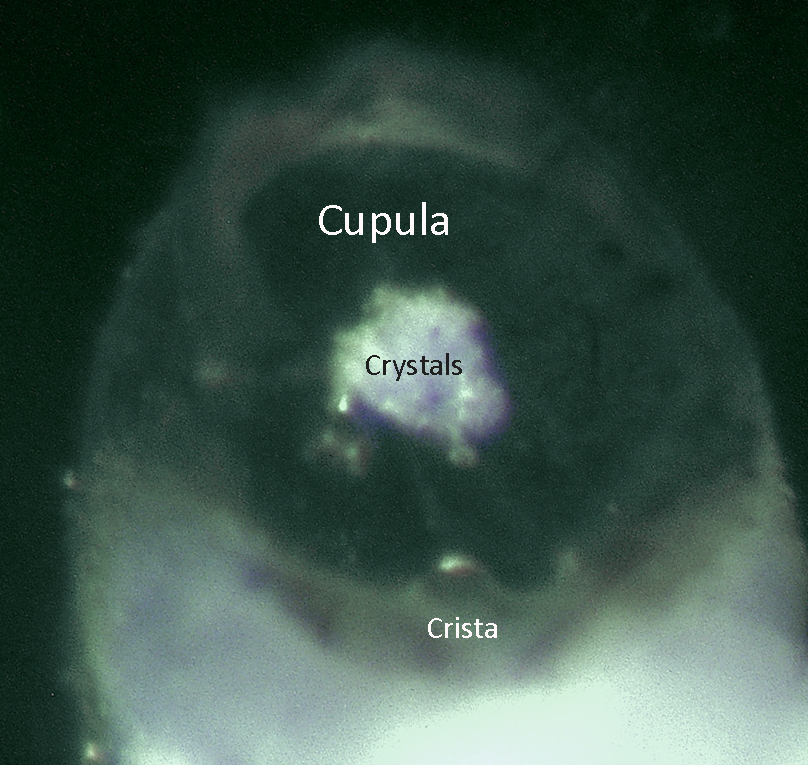

Here’s a photograph of the cupula of a mouse, taken by Dr. Olivia Kalmanson at the University of Colorado. The cupula looks dark green because it’s transparent, so the background can be seen right through it. To make it easier to see, we’ve piled otoconia, the gravity sensor’s crystals, on the middle of it. They are indenting it like a pile of rocks would indent a trampoline. At the bottom of the picture is the crista, the base of attachment of the cupula that contains all the nerves and sensory cells that make the inner ear able to sense spinning.

Continue reading “Why is HBPPV such a problem?”Cupulolithiasis in BPPV: Rare, or non-existent?

Newsflash: Read our science article, Cupulolithiasis: A Critical Reappraisal, at http://doi.org/10.1002/oto2.38

BPPV is the best understood form of vertigo, and usually goes away promptly with simple maneuvers. Sometimes, though, it can persist, and in those cases, a somewhat different and rare form is diagnosed, called cupulolithiasis. This means “stones on the cupula”, the cupula being the main sensor of the inner ear. In the time before we knew that ear stones—otoconia—moved freely in the ear canals causing vertigo, there was a theory that all the symptoms of BPPV were caused by otoconia that were attached to the sensor itself. Does this really happen?

Continue reading “Cupulolithiasis in BPPV: Rare, or non-existent?”