Dr. Foster will be interviewed tomorrow (Wed. May 21st) about vertigo and imbalance on Sirius XM “Doctor Radio” channel 110.

The 1-hour program begins at 11 am mountain time and is a nationwide call-in. See you there!

Tips and tricks to conquer dizziness

Dr. Foster will be interviewed tomorrow (Wed. May 21st) about vertigo and imbalance on Sirius XM “Doctor Radio” channel 110.

The 1-hour program begins at 11 am mountain time and is a nationwide call-in. See you there!

I’ve had plenty of vertigo in the past, but I wasn’t dizzy at all when I fell. I just bent over to pick up a heavy pot, and tipped right over. Sometimes when hiking on hills I’ll lose my balance, and I’ve fallen a couple of times. I’m in my 70’s, is this normal?

Read more: Help! I fell after bending overFalling never seems normal, but it becomes more common as we age. All parts of our balance systems begin to decline, and gradually it becomes easier to fall. That means you have to take active steps to prevent hurting yourself.

One of the most common balance problems comes from a gradual loss of sensation in the feet and lower legs. The nerves that supply the feet have to stretch from the spine, where the main part of the neuron resides, all the way to the feet. Any problem along this extension can result in a loss of feeling, and this is frequent in older people. Get a cold metal object like a heavy spoon and run it along your fingers; you can easily feel the cold. Now run the same spoon over the bottom and sides of your foot. If you find numb places, or don’t feel the cold as strongly, you are losing sensation in the feet. This can also be tested by placing a vibrator or vibrating tuning fork on your feet and comparing that to your hands. A loss of vibratory sense correlates with a general loss of sensation.

Why would losing sensation in the feet make you more likely to fall? The three components of the balance system are the inner ears (which sense movement of your head in space), your eyes (which can see whether you are upright, moving or tilted), and the feeling in your legs and feet. Even if your inner ears are functioning well, you still need some input from the other two systems.

When you bend over, you can no longer use vision for balance as well. Normally we use the horizon, or vertical objects near us, to measure whether we are stable. If we are still, the horizon stays horizontal and vertical things like trees or walls look upright. If we bend over to look at the ground, we lose that vertical and horizon orientation. It’s much harder for the balance system to detect a bit of tilt in that position.

That forces us to rely upon the feeling in our legs and feet for balance. If I can feel the ground, and tell whether my ankles are bending, then I know I am stable. It doesn’t take much loss of feeling to make this less effective. A little numbness makes you more likely to fall when you bend or focus on the ground instead of the world around you. You also become more likely to fall when in the dark.

Fortunately there is something you can do when this happens. In most people, sensation remains very good in the hands even if they lose some in the feet. By touching something stable like a wall or post, the tendency to tip over when bending forward will be stopped. Using trekking poles in the hands while walking has a similar effect. You will basically be bypassing your numb feet and allowing your hands to feel the ground through the pole, which will restore your balance.

My latest paper with co-author Olivia Kalmanson just came out and can be read here. It’s about an ongoing confusion regarding how BPPV (positional vertigo) causes its symptoms. This confusion has been going on for over 50 years now. This kind of problem is very common in science. It begins when a prominent researcher publishes a theory that will turn out to be wrong. However, because the person is prominent, people are afraid to criticize the mistake. In fact they keep putting it forward long after other, less well-known scientists have come up with a much better explanation. Decades go by, long after the first theorist is in the grave. Eventually the sheer weight of evidence crushes the incorrect theory, upholding the self-correcting nature of science. Sadly though, much time is wasted.

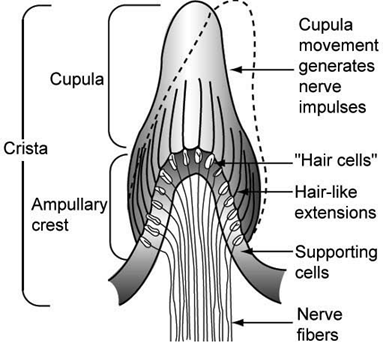

Read more: Our latest BPPV paperThe old theory we are talking about in our paper is cupulolithiasis, the belief that the particles in the inner ear that cause BPPV attach strongly to the cupula, the spinning sensor of the inner ear. These particles are heavy, causing the sensor to respond to gravity. Seems quite reasonable at first. Part of the reason this caught on easily was misunderstanding the anatomy of the sensor.

This is an older anatomy picture that was how most people visualized the sensor in the past. The cupula was pictured like a little flame, with a wide base and a narrow tip that swept from side to side. It was this sweeping movement that was thought to move the hairs at the base, sending electrical signals that the head was moving. It seems simple to just stick a clump of particles on the tip, which would cause it to bend with gravity.

This isn’t how it looks or works. The cupula is an oval membrane that is attached at the base, the ampullary crest in this picture, but is also attached all around its rim to the ampulla, a sphere that surrounds it. It’s more like a trampoline than a flame. The reason this has been hard to understand is that, first, the ampulla is only about ¼ inch across so all of this is nearly microscopic. Secondly, it is completely encased in the bone of the skull, so it is not seen unless you use a drill. Finally, it is nearly transparent. No wonder the anatomy is confusing.

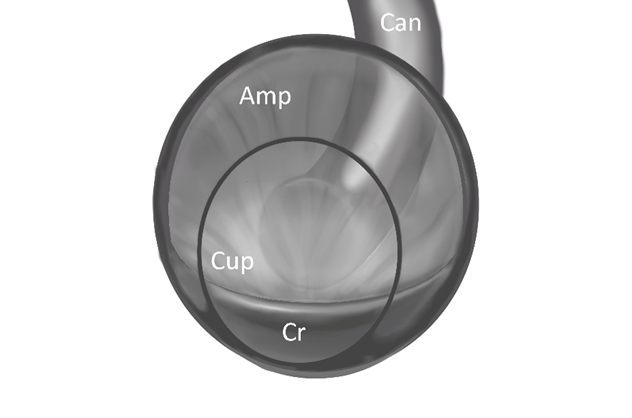

Here is a more modern view:

Viewing straight on at the cupula “Cup” , you can see it is an oval attached all around the edge to the ampulla “Amp”. The canal “Can” that contains the crystals in BPPV is pointing at it from the back in this picture. Crystals couldn’t attach to the tip because there is no tip. If they stuck anywhere, it would have to be the middle. They would have to be very sticky indeed to stay on a constantly flexing mat, resisting the pull of gravity.

The theory that particles stick on the tip and move the cupula was published in 1969 by Schuknecht, who was a very prominent and intelligent physician scientist. It wasn’t a bad way to explain BPPV at the time, and many of the other things he figured out were good. However, about a decade later, McClure and his team came up with a better solution: that crystals were moving back and forth in the canal, working like a piston that could move the canal fluid back and forth, and this would flex the cupula like a trampoline. Loose particles could be rotated out of the canal, and this was proven by Epley, who invented a curative maneuver. They were correct, but by then almost everyone was still enamored with the cupulolithiasis theory and respectful of its author. The better theory was not accepted for another decade. Even then, cupulolithiasis remained popular too, especially for BPPV that didn’t respond well to maneuvers.

Over time it’s become clear that these resistant cases can be explained by blockages that form in the canals near the ampulla or at narrowings, trapping particles. They don’t need to stick to the cupula to cause symptoms. So cupulolithiasis is no longer needed to explain BPPV.

Even though it’s unlikely that two totally different mechanisms for a disease will turn out to be true, there are still articles being published about cupulolithiasis 56 years later. The problem, though, is that everything in BPPV can now be explained by particles in the canal. Belief in cupulolithiasis is holding the field back. This is important because the treatments needed would be different. If you have loose particles in the canal, you can move them out with maneuvers. If there is a blockage, some vibration on the head can help break it up. If they were attached to the cupula, however, this would not necessarily work. Finding an effective treatment depends on truly understanding how the system works.